Posted January 11, 2026

Written by Nicholas Hellmuth

We start off the New Year (2026) with two helpful photos from Javier Archila of the resplendent quetzal, Pharomachrus mocinno, the national bird of Guatemala and a sacred bird for thousands of years. Javier photographed these birds during October 2025, at Ranchitos del Quetzal, Baja Verapaz. The FLAAR team has also stayed at this hotel in previous years to photograph the quetzales which occasionally fly to the surroundings of the hotel (so you don’t have to climb steep hills elsewhere).

We are studying all animals that are featured in Maya art, especially artifacts and textiles exhibited in the national museum of archaeology and ethnology of Guatemala to prepare educational material for students who come by the thousands to visit this museum. Many authors of the previous century captioned birds associated with Early Classic incensarios as “quetzal” but by studying quetzales we realize that although this sacred quetzal bird is present in Maya artifacts—and lots in Maya weaving of today—the bird that is on incensarios is an owl. The other more common creature on these Early Classic incense burners has long been recognized correctly as a butterfly.

So we have a lot to study during 2026—how many different species of butterfly, or moth, are on incense burners. Most writers call it the black witch moth—but if you look at the dozens, scores of butterflies on the endless numbers of incense burner lids you see that many different species are pictured and I estimate a lot are butterflies—not a black witch month.

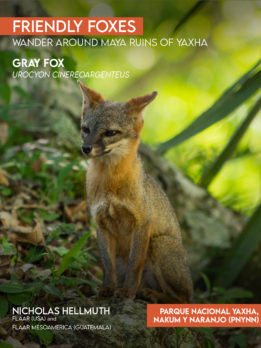

Another challenge is to learn how many different species or regional variants of pre-Hispanic dogs appear in Maya art. I estimate at least three different sizes, shapes and fur patterns were present (but I may revise or expand this estimate after more research).

Jaguars have been a research topic for decades, and we have learned that lots of the feline pelage designs on Maya ceramics are NOT jaguar—but are patterns of ocelot, Leopardus paradlis.

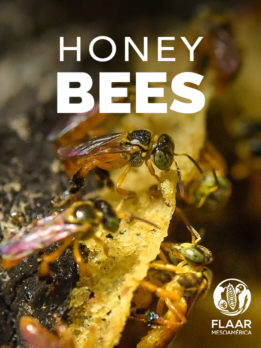

We have been studied insects in Maya art for the recent three years since most captions for scenes of Late Classic insects just dump them as “bee” which is 90% of the time incorrect. More than half the insects in Maya art have not yet been named correctly. So a lot more research.

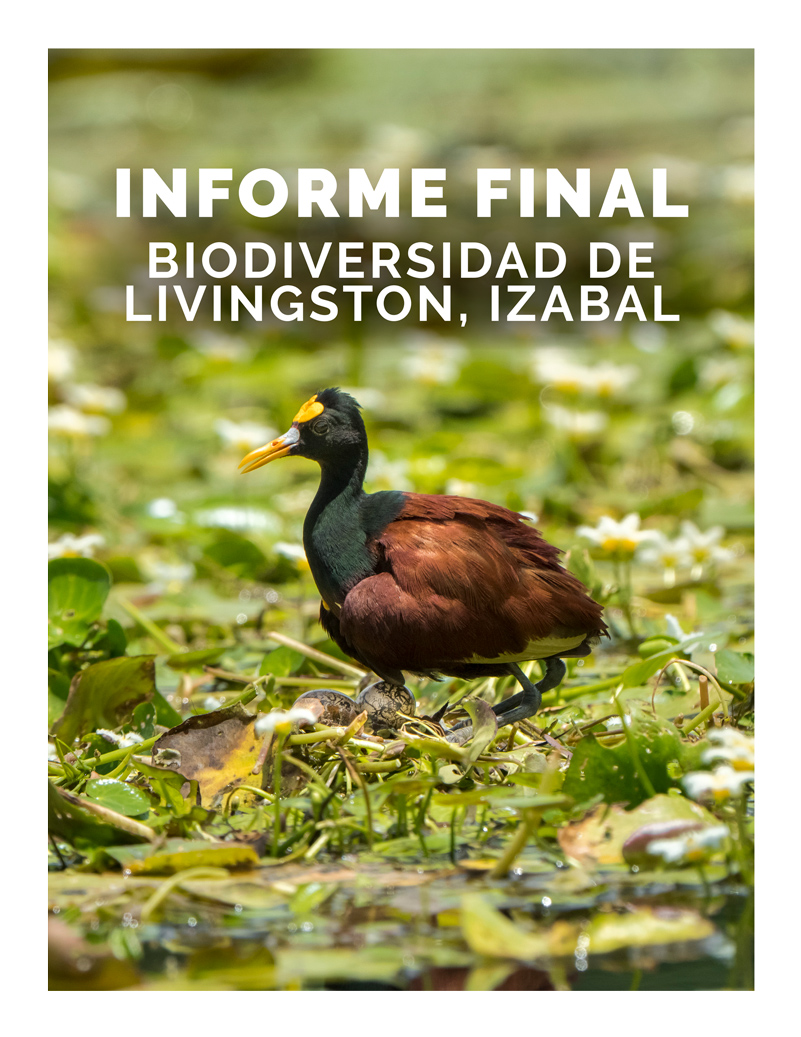

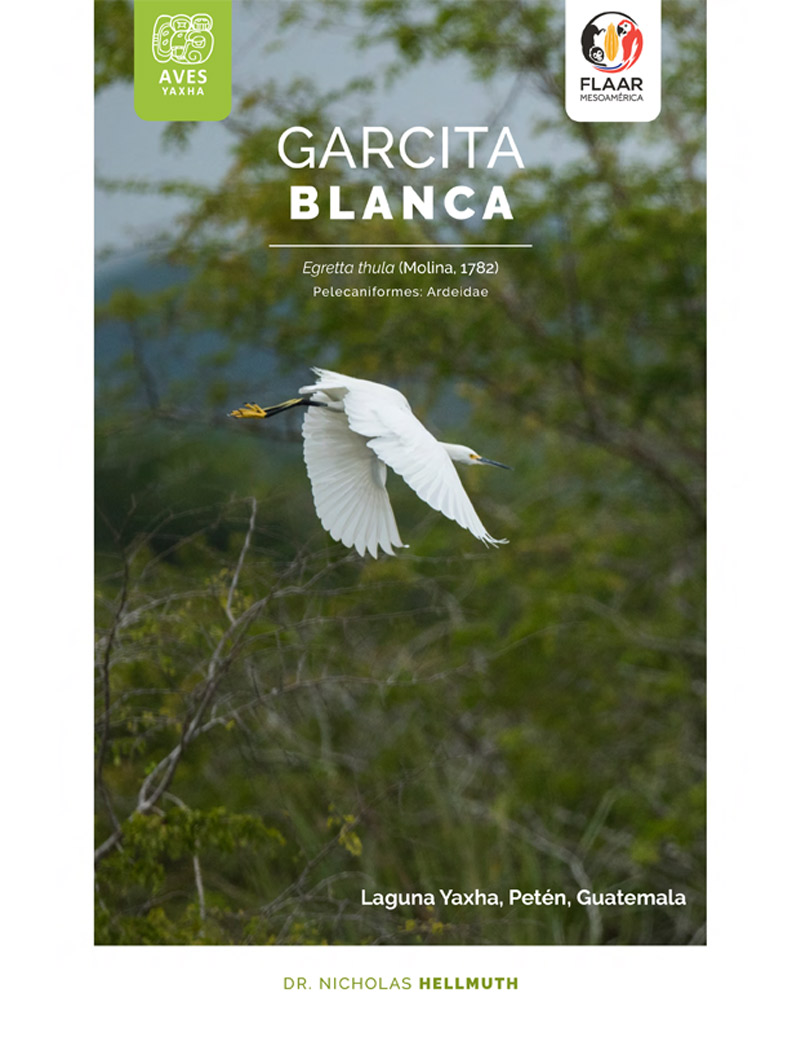

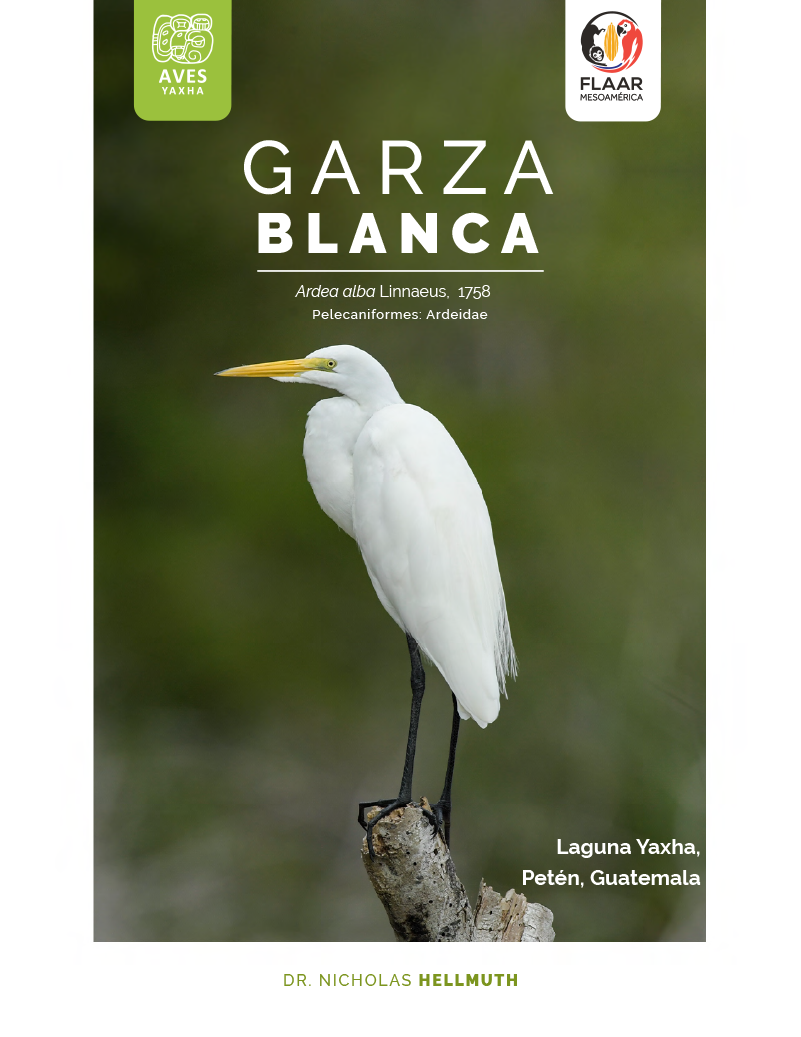

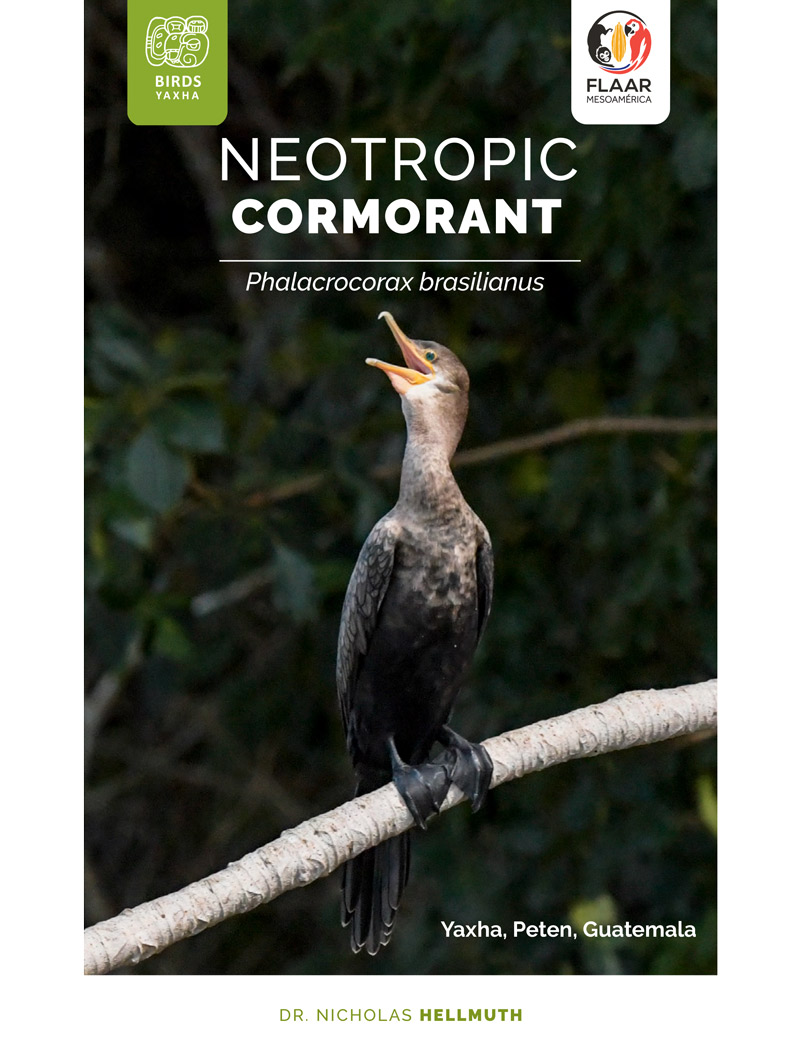

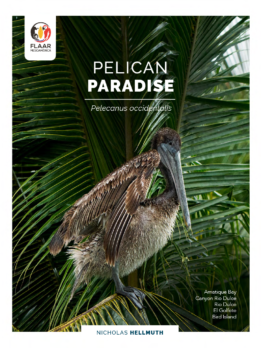

I have been studying waterbirds since research in the 1980’s for my 1986 PhD dissertation (published in 1987), and we continue this research. We will be documenting a lot of advances later in 2026.